The 1920s

PPL is born

PPL, originally called Pennsylvania Power & Light, was formed on June 4, 1920, when eight utilities merged into one. The company, which had 62 power plants, became a model for the mergers and consolidations that occurred throughout the electric utility industry during the 1920s.

1920

Influential leader becomes company’s first president

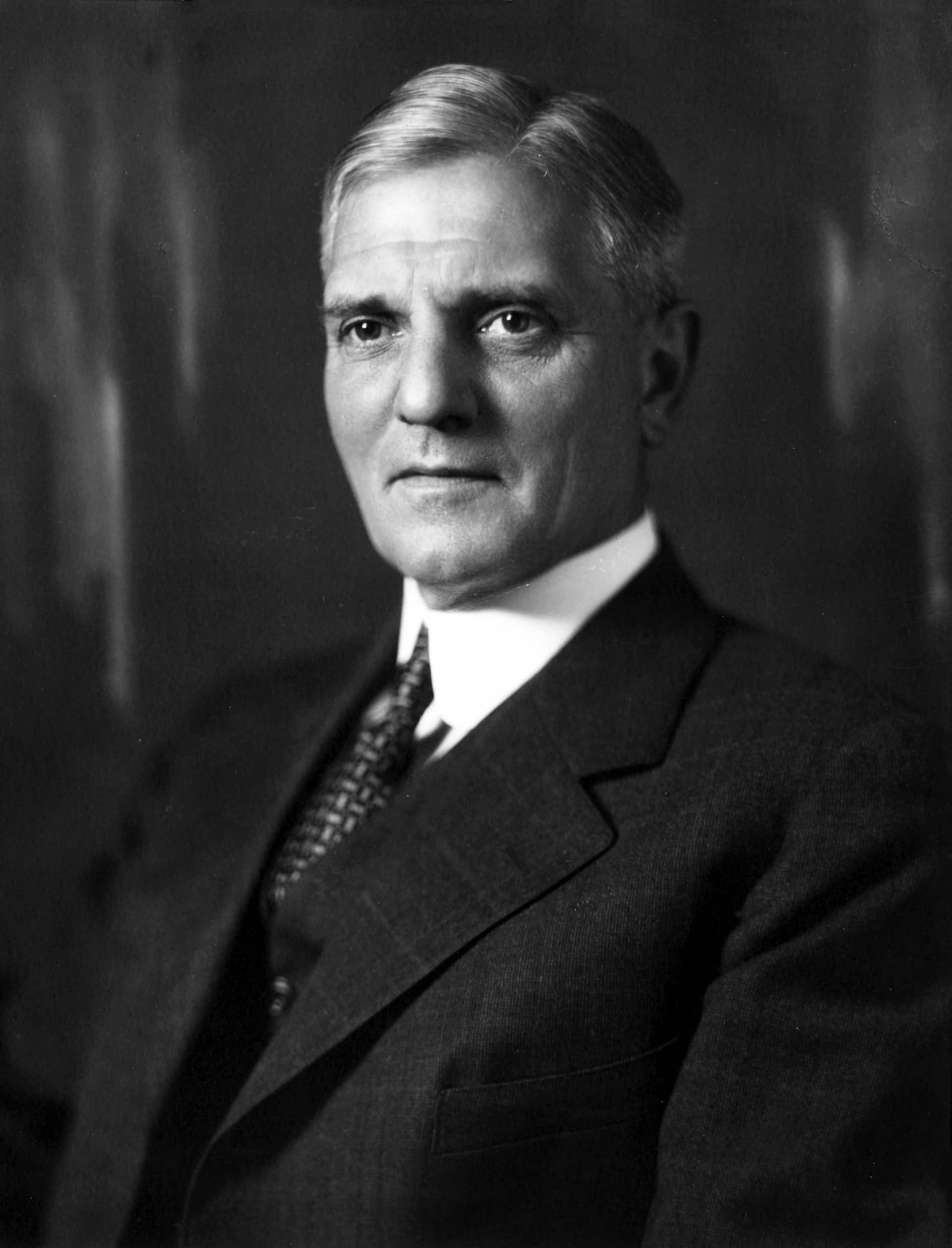

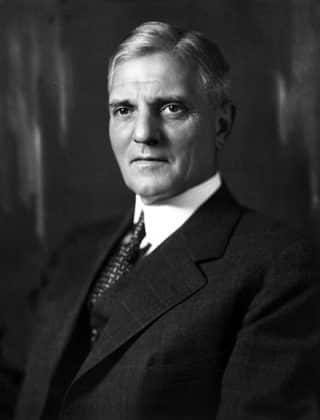

PP&L’s first president, Edward Hall, guided the company through its initial stages of growth. Hall was also one of the founders of the modern game of football.

Edward Hall

1926

New plant creates landmark lake

The Wallenpaupack hydroelectric plant is put into service, creating Lake Wallenpaupack, a 5,760-acre lake that is a mile wide, 16 miles long and 60 feet deep. The new hydroelectric power plant was capable of producing 40,000 kWh of power. To use this power, PP&L launched an effort to upgrade its transmission system and substations.

A kayaker paddles past the Lake Wallenpaupack hydroelectric dam. Photo courtesy of The Times-Tribune.

1928

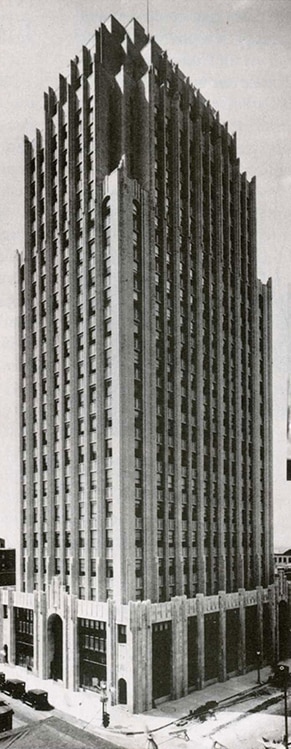

PP&L’s iconic Tower Building is erected

PP&L’s headquarters inspired the design of the Rockefeller Center in New York City. It has become an icon in the Lehigh Valley and an anchor in Allentown, Pennsylvania’s skyline. Within its walls, the Tower building holds fascinating artifacts and stories.

1920

Influential leader becomes company’s first president

PP&L’s first president, Edward Hall, guided the company through its initial stages of growth. Hall was also one of the founders of the modern game of football.

From the gridiron to PPL’s grid, Edward Hall left an enduring legacy

PP&L’s first president had a major role in setting the company up for success for years and even decades to come.

Under Hall’s guidance, the company – then called Pennsylvania Power & Light Company – consolidated a group of electric and gas companies serving central Pennsylvania and acquired an additional 39 companies in northeastern PA between 1923 and 1928.

During Hall’s presidency, the company also negotiated with Scranton Electric Co. for the construction of the joint-venture Stanton Steam Electric Station and it was Hall who started planning for the construction of PP&L’s iconic Tower Building in downtown Allentown in 1928.

And setting PP&L up for success isn’t even what Hall is best known for.

Hall’s major claim to fame is helping shape the modern game of football.

After a spate of brutal college football injuries and even deaths around 1905, U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, an avid football fan, wanted changes in the sport. He met with college presidents who agreed to form a rules committee for intercollegiate college football. Hall – a former captain of the Dartmouth College football team and later coach at the University of Illinois – was selected as a member of the committee in 1905. He became the committee’s secretary in 1907 and its chairman four years later – a position he held until his death in 1932. He championed the forward pass, which came to prominence in 1913 and transformed the sport. Hall also pushed for safer play, including the abolition of the flying wedge – in which teammates would lock arms with a ball carrier and drive him to the goal line – and other plays that led to serious injuries.

Hailed as “the father of modern football,” Hall was inducted into the Football Hall of Fame – later renamed the College Football Hall of Fame – posthumously in 1951.

While shaping football, Hall earned his law degree from Harvard Law School and practiced law for about 17 years before becoming vice president of New England Telephone and Telegraph Co. in Boston in 1912. Five years later, he became vice president of personnel and a director of Electric Bond and Share Co. in New York City and he later became a vice president for AT&T.

Those opportunities led to his eventual job as PP&L’s first president, a position that added to Hall’s already impressive resume.

Hall’s background as a lawyer served the company well during the mid-1920s when Pennsylvania Gov. Gifford Pinchot’s “Giant Power” program suggested the municipalization of the state’s electric utility industry. Aside from helping to stiff-arm that attempt and overseeing key consolidations, acquisitions and the early plans for the construction of the Tower Building, Hall was also at PP&L’s helm when the Wallenpaupack hydroelectric project in the Pocono Mountains was built. The plant created Lake Wallenpaupack, a 5,760-acre lake that tourists continue to flock to today.

Hall left PP&L in 1928, eight years after taking over as president. He left an indelible mark on the company – just like he had for the game of football.

1928

PP&L’s iconic Tower Building is erected

PP&L’s headquarters inspired the design of the Rockefeller Center in New York City. It has become an icon in the Lehigh Valley and an anchor in Allentown, Pennsylvania’s skyline. Within its walls, the Tower building holds fascinating artifacts and stories.

PPL’s Tower Building: a constant in a city of change

Downtown Allentown has changed greatly in the last 92 years, but PPL’s Tower Building has remained a constant — a beacon of progress defining the city skyline.

By 1925, PP&L had outgrown office space at the Buckley Building, 502 Hamilton St. Departments were scattered throughout Allentown, and the need for a central location was clear. Thanks to board member Gen. Harry Trexler’s persuasiveness, the decision was made to keep PP&L in Allentown. Negotiations on the Ninth and Hamilton site began that year.

Don Cunningham, president and CEO of the Lehigh Valley Economic Development Corporation and a former PPL employee, says the Tower Building has since become a bedrock of Allentown.

“I think as a former mayor and county executive, the idea that PPL has never left … that is tremendous for the region and the city,” Cunningham said. “No matter what difficult time the city’s gone through, having the tower there and PPL there, represented a foundation that wasn’t going away.”

Building a foundation

The architectural firm behind New York’s Bush Tower — Helmle, Corbett & Harrison — was hired to design PP&L’s 322-foot-high, 23-story skyscraper. Wallace K. Harrison and Harvey Wiley Corbett set to work on the $3.2 million building; Harrison later called it “Harvey Corbett’s great building.”

Harrison’s portfolio would later include the United Nations Building and Lincoln Center among others. He and Corbett also collaborated on Rockefeller Center in New York City — which he partnered with Corbett on, and bears similarities to the Tower Building.

Upon completion in 1928, the Tower Building boasted a frame of 5,700 tons of steel, more than 2.8 million bricks, 42 miles of piping and 104,200 bags of cement. Allentown was the second city in Eastern Pennsylvania (after Philadelphia) to adopt electric lights for hotels and businesses in the 1880s, so it was only fitting that the Tower debuted with more than 1,600 electric lights inside.

Signature features

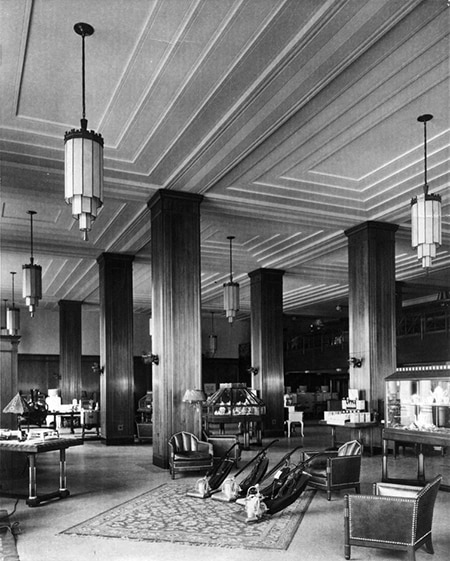

PP&L debuted the art deco-style building with a five-day public open house with waffles and coffee for guests. Visitors marveled at the building’s modern amenities, including the first private automatic or “dial system” exchange communications system in Allentown, elevators that soared to the top in less than 30 seconds and a sales floor with the latest home appliances.

The tower’s sleek lines caught many eyes. Its unique design earned a spot in The Encyclopedia Britannica in 1930, as “the perfect example of the modern skyscraper.”

The facade was also used to depict the fictional Tredway Corporation in Robert Wise’s movie “Executive Suite,” which debuted in 1954. Details for how the tower was selected aren’t clear. But a librarian with the Cinematic Arts Library at the University of Southern California found a copy of the director’s original script, which calls for “a sky-thrusting shaft of dazzlingly clean white stone, rising an incredible 24 stories above the drab, low-lying buildings that surround it,” with Allentown scrawled in red pen next to it.

An outdoor gallery

While the building’s interior was richly appointed in terrazzo stairwells and marble washrooms, the exterior gleamed with bronze work and sculptural reliefs by Alexander Archipenko, a famous cubist contemporary of Pablo Picasso.

Today, Archipenko’s work can be found in the collections of the Guggenheim, the Smithsonian and the Museum of Modern Art. Corbett wanted to adorn his modern building with modern art and gave Archipenko his first major U.S. public commission.

Some of Archipenko’s reliefs reflect fish and gears, which are thought to symbolize hydroelectric power. Others feature animals and folk tales. Reports indicate Archipenko sketched in Allentown, but carved at his New York studio and shipped panels by train back to Allentown. The Archipenko Foundation in New York is currently researching the sculptures for a Catalogue Raisonné project that started in 2018.

Through it all, PPL’s Tower Building has remained an icon. With the 2019 demolition of Bethlehem’s Martin Tower, which debuted in 1973 and eclipsed the Tower Building by 10 feet, PPL remains the tallest building in the Lehigh Valley.

“Companies can come and go. Buildings can come and go,” Cunningham says. “So, it’s quite amazing that this really cool, art deco building that was built in the ‘20s is still there, still in full use by the same company.”